OBEISANCE AND HOMAGE TO MARTYRES

नमन और श्रद्धांजलि

THE SIKHS THE MUGHALS AND THE MOHYALS

By R. T. MOHAN

This narration is dedicated to the following Mohyal associates of the Sikh Gurus, who were tortured and martyred by the Mughals because they refused to give up their own faith and convert to Islam.

- Baba Prag Das (1507-1638): Although advanced in age, respecting the wishes of Guru Hargobind, Baba Praga took up arms against Painde Khan, the Mughal Subedar of Lahore and defeated the Mughal army. He was wounded seriously in this battle and died after returning to Karyala.

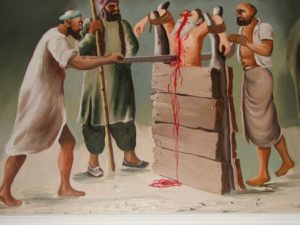

- Bhai Mati Das: 9 November, 1675. He was bolted between two wooden planks and bifurcated into twain ,with a saw. He bore this torture with equanimity.

- Bhai Sati Das: 10 November, 1675. He was roasted alive, with oil soaked cotton wrapped around his body and set afire.

- Dewan Sahib Singh. In a battle against Mughals near the river Beas, which the Sikhs won, he was martyred. Guru Gobind Singh himself cremated the body of Sahib Singh. A memorial was erected there.

- Dewan Dharam Singh. Likewise, Dharam Singh, also a Dewan under Gobind Singh, was martyred in a battle.

- Mukand Rai/Singh, son of Bhai Matidas. ) Both of them were martyred, along with

Kirpa Ram/Singh Datt of Kashmir. ) two sons of Gobind Singh, when surrounded by a large Mughal army, at the battle of Chamkor. The Guru managed to escape.

- Lachhman Dev, a.k.a Banda Veer Bairagi, )19 June, 1716. The Mughal tormentors

Son of Ram Dev Chhibber of Mendhar ) devised methods of torture more

excruciating than those applied to Matidas and Satidas. Banda remained calm during those tortures.

- Gurbaksh Singh. After Guru Gobind Singh proceeded to Daccan, his Dewan Gurbaksh Singh, came to Amritsar. He was martyred fighting, when Ahmad Shah Abdali of Afghanistan, in one of his invasions, attacked Amritsar to destroy the Golden Temple.

Except those at nos. 7 and 8, all these martyrs were scions of the Chhibber family of Karyala, descendants of Baba Prag Das. The chain of martyrdom does not end here. Balmukand Chhibber of the same Karyala Chhibber family was hanged on 5. November, 1910, for throwing a bomb at the British viceroy.

—–*—–

Bhakti Movement

Religious oppression by the Sultans of Delhi and their bigoted subordinates had depressed the Hindu masses to the abyss of dejection. During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries arose Bhakts and Sufis in Northern India, like Farid, Kabir and Nanak, who tried to conciliate the religious friction. They preached equality of all religions and need for mutual tolerance.

During the same period another galaxy of Hindu Bhakts preached passionate devotion and attachment to their sagun avatars (the god incarnate): Surdas (1483-1563), Chaitanya (1486-1533) and Mira Bai (1498-1531) for Lord Krishna; Tulsidas (1532-1623) and Ramanand (14-15th century) for Lord Rama. Their soul-touching devotional bhajans (hymns) in simple language soothed and enchanted the tormented souls. Just hum and feel the effect of these melodies (visualising the face of an innocent but nutkhut Shyam): Maiya! main nahin maakhan khaayo … ; Maiya! mujhe Dau bahut khijaayo … ; Mere to Girdhar Gopal, doossro na koi … Can any worries overwhelm you in the company of this playful Girdhar Gopal? There sprang up a bond of devotion and intense personal attachment between the bhakts (devotes) and their Araadhya Deva – the Lord of their prayers. Through these adorations they felt so close to their Creator. With this bond established, the oppressed soul could fervently appeal to the All Powerful and Merciful Lord for protection: Deen Dayaal virudh sambhari, haro Naath mum sankat bhaari. The suppressed people gained a feeling of self-respect and courage to face their tormentors. The Marathas, the Bundelas, the Jats and the Sikhs all gradually rose like lions. Guru Nank was the harbinger of such change in Punjab.

Guru Nanak and his time

Nanak, the founder of the Sikh faith, was born in the year 1469 at Talwandi Rai Bhoe (now named Nankana Saheb) about forty miles from Lahore. His father Mehta Kalyan Das Bedi was an accountant in the village. As usual in those days, Nanak was sent to a Pandit to learn Sanskrit and to a Muslim Maulvi for Persian but he took little interest in his studies. Later, Nanak held a modest job under provincial government for eight years, married and had two sons – Srichand and Lakhmichand. But he did not want to lead the life of an ordinary Grahastha (householder). He was of a meditative and pious disposition. He seems to have been deeply troubled by the religious, social and political conditions and has left a succinct record of his feelings.

By then, Punjab had been under foreign domination for a few centuries and the history of the period has already been briefly stated.[i] Sultan Sikandar Lodi (1489-1517) was reigning at Delhi. The Bhakts and Sufis had been trying to conciliate the aggressive Islam and native Hindu religion by highlighting the need for devotion (bhakti) to God, and excellence in behavior, as the central theme of both religions. We have already narrated the fate of the unfortunate Bangali Brahmana (named Bodhan) who paid with this life, at the command of Sikandar Lodi for “propagating peace”. (How would Islam

Ferishta relates heart rending stories of destruction, by Sikandar Lodi, of temples in Mondril in 1504 and in Hanumangarh in 1506. In Mathura he destroyed the temples and replaced them by caravanserais and mosques. He even deprived the Hindus of elementary rights of citizenship by forbidding them from taking bath at the sacred river of Jamna. “Corruption, degradation and treachery stalked openly through the market … Honour, justice and position were bought and sold. The rulers of the land were sunk in voluptuousness in the abyss of enfeebling debauchery.” (Mohammad Latif)

Nanak himself has described the prevailing situation in these words:

Kings are butchers, cruelty their knife,

Justice has taken wings and fled.

Falsity prevails and moon of truth

Is visible nowhere.

I have tried myself in searching about,

But in the darkness no path is visible.

The world is suffering an endless pain in ego,

How shall it be saved? sayeth Nanak.

(Majh ki Var)

Looking for a path in the darkness, Nanak undertook extensive travels in India and abroad. Starting in 1496, he visited all the holy places of Hindus in India. He is also stated to have visited Arabia and Baghdad. He is believed to have held discussions with the learned men, trying to understand all faiths.

Meanwhile Babar made several forays into India, before defeating Ibrahim Lodi at Panipat in 1526. In 1520 Babar marched up to Sayadpur, where the garrison offered some resistance. The retribution was awful. The entire garrison was massacred and the inhabitants of the place were butchered or carried away into slavery. An eye-witness to the holocaust, Nanak wrote at the painful sight:

Dhan jauban dui bery hoye, jin rakhe rang laye,

Dutan no pharmaiyan lai chal pat ganvaye.

“Wealth and beauty of women, both proved to be their bane; they were forcibly taken away and dis-honoured”. Finally when Babar conquered India, shedding a lot of innocent blood, Guru Nank declared in his poignant verses:

When Babar’s rule was proclaimed no one could eat his food,

If a powerful person were to attack another powerful person,

There shall be no anger in my mind,

But if a ferocious lion falls on a herd of cattle,

The master of the herd should show his manliness.

Tears of blood must have run down the eyes of the Guru, who saw the havoc brought about by Babar:

Jaise men aave khasam ki baapi, taise karen gyan, ve Lalo!

Paap ki janj lai Kablon dhaaya, jori mange daan, ve Lalo!

(Granth Sahib, Tilang, Mohala 1, page 722)

Referring to Babar as bridegroom who had come from Kabul with a party of sins, he was demanding forcibly the gift of bride – the Indian Empire.

Khorasan Khasmanan ki aa Hindustan draaiyo,

Aiti maar pari kurlane tain ku darad na aaiyo.

(Granth Sahib, Raag Asa, Mohala 1, p. 360)

The Lord of Khurasan has come to intimidate Hindustan, the tortured populace is crying with pain but there is no mercy. Nank further records: “Modesty and righteousness all vanished and falsehood held the chief authority. In the plunder both Hindus and Muslims were treated alike. The Muslim women read the Quran and in agony called God for help. And so did the Hindu women. There was a blood shed all around.”(Granth Sahib, Raag Telang, Mohala 1)

What was the solution for debasement in society? Nanak travelled far and wide seeking solution. On his return he started gathering sangats (congregations) and preaching his ideas through recitation (kirtan) of his hymns – he composed 974 in all. In the tradition of Kabir, Nanak assailed at once the worship of idols, the authority of the Quran and the Shastras and the exclusive use of learned language (Sanskrit and Arabic). Like Kabir, he spoke to people in their everyday language. Guru Nank passed away in 1539.

MOHYAL DISCIPLES of GURU NANK

Baba Prag Das

In these disturbed times, there was another person with tormented soul who was seeking purpose and direction in life. His name was Prag Das. As stated earlier, Mohyals inhabited the region between the rivers Sindh and Jhelum. This comprised the first leg of the highway connecting Attock with Lahore. It was the first line of defence of Delhi Sultanate, usually poorly defended. Invaders were always coming from the north-west, killing, looting and enslaving as they came or returned. Mohyals as a warrior race, could not enjoy peace after they ceased to be the rulers of the region in the beginning of the eleventh century.

One Raja Tharpal Chhibber, descended from the stock of Raja Dahar of Sindh, was in search of a suitable place which could be defended when the marauding Mongols or Afghans passed that way. He selected a place in the cradle of the Salt Range, not far from Nandana, the garrison fort of Trilochana Pala Vaid which had been destroyed by Mahmud Ghaznvi in 1014. Raja Tharpal built a fort there called Garh Thar Chack. It was located on the bank of Gambir nadi (river). This was during the time of Bahlol Lodi (1451-1489). Goutam, son of Tharpal died in a battle against Babar in 1519.[ii] One of his sons, Prag Das, was then only twelve years old.

Prag Das was of a saitly disposition and spent several years in tapassaya – seeking enlightenment. He met Nanak when the Guru was preaching his message in Kashmir. He was baptized into Nank Panth (Sikhism) and was henceforth named Baba Praga. Nanak advised him to lead the life of a grahasth (householder) instead of becoming an ascetic (sanyasi) in the prime of his youth. Baba Praga returned to his ancestral place Thar Chack, selected a suitable location and established the village Karyala. He married the daughter of Tara Chand Vaid, Dewan of Fort Sarang (near present day Campbellpur).

Baba Praga remained close to the Sikh Gurus. During the investiture ceremony of Guru Arjan, Baba Praga again sought spiritual advice. The Guru advised him to shun outward ceremonial worship and rituals. He further initiated Praga into Yog, for “interior grace”. During Pranayam or rhythmic breathing, Praga was to invoke the sacred word “OM” at the time of inhalation and “Swaha” while exhaling. (Russel Stracey)[iii] He had a very long life and the gurus continued to avail of the devotional as also martial skills of this Warrior-Brahmana. Baba Praga sired a family, several members of which served the gurus and sacrificed their lives at their command. Durga Das was son of Prag Das. Pera Chhibber, another son of Goutam, (and brother of Prag Das) also remained in the service of Sikh Gurus. Chaupat Rai/Singh and Chhote Mal (particularly his son Gaval Das) were like members of the gurus’ families.

Kirpa Ram Datt of Kashmir

Another person who came in touch with Nanak in Kashmir was Brahm Datt – Mohyal Brahman of Bhardwaj gotra. He started preaching Nank’s Panth, which work was carried on by his descendants: Narayan Das (son), Aroo Ram (grandson) and Kirpa Ram (great grandson). Sarasvati, mother of Kirpa Ram Datt was the sister of Bhai Praga and Bhai Pera, Chhibbers of Karyala. (Vahi Pandit Govind Das of Haridwar). Kirpa Ram Datt had proficiency in Ved, Vedang, Jyotish, Puran etc. True to his calling as a Mohyal Brahman, he was also an accomplished warrior. (He died during the battle of Chamkaur). Guru Hargobind assigned to him the duty of educating the children. He performed this duty up to the time of Gobind Das (later Guru Gobind Singh). Like a member of the family he travelled with the families of the gurus, while his own family preached the religion of Nank in Kashmir. He taught Hindi and Sanskrit to Gobind Das.

Angad, Amar Das and Ram Das, the next three Gurus, expanded and consolidated the Sikh church. The institution of langar (free kitchen), Gurmukhi script, setting up manjis (parishes) at different places and appointing Masands (agents or managers) were some of the measures undertaken. All of them wrote more hymns which were included in the Granth SahIb.

A successor was nominated by a Guru and now succession had become dynastic. Ram Das, a Khatri of Sodhi caste, had his youngest son Arjun anointed as the fifth guru, when he felt his end was near. Several siblings who were overlooked continued to create trouble for the gurus. Bhai Pera, brother of Baba Praga, was a member of the Panchayat of Guru Arjun. Prithmichand, Guru Arjan’s brother did not accept his father’s choice of successor and continued to create trouble. Bhai Pera helped in warding off evil designs of Prithmichand. Arjun has several important developments to his credit. Harimandir was built at Amritsar and its foundation stone was laid by Mian Mir, a Muslim divine. A pool, Amrit-sar (the pool of nectar) was constructed alongside, giving the Sikhs their own place of pilgrimage. Granth Sahib was compiled as the holy book of the Sikhs. Apart from the hymns of the gurus, contributions from different Hindu and Muslim poet-saints of North India, like Shaikh Farid, Kabir, Namdev and Ravidas, were also included , if these were in consonance with the tenets of Nanak and their language simple. Arjun built several towns – Taran Taran, Kartarpur and Hargobindpur – apart from Amritsar.

Mughal Emperors were understandably apprehensive about the growing Sikh community, owing allegiance to one leader, their guru. There were also reports that some of the Sikh sacred literature was anti-Islam. Akbar paid several visits to the Sikh Gurus. He did not find anything objectionable in what he observed or was sung in his presence. The Granth had not been compiled till then. He made some offerings after each visit. Emperor’s admiration helped in building Sikh fortunes. The trade thrived in the four towns that Arjun had built. The jat peasantry joined the Sikh church which grew rich and powerful. The Guru was now addressed as the Sacha Padshah (the true Emperor).

The death of Akbar brought a sudden reversal in the liberal policy of the Mughal state towards the Sikhs – and indeed all non-Muslims. This had disastrous consequences for the Sikhs. Guru Arjan Dev was martyred during the reign of Jahangir. Jahangir has himself recorded the tragic account of the end of the Sikh Guru in these words:

In Govindwal, which is on the bank of Beas river, there was a Hindu named Arjan who by assuming the garb of a (religious) guide and instructor (Pir-o-Shaikh) has made a large number of simple Hindus and even of ignorant and foolish Muslims into followers of his own ways and practices and had trumpeted abroad his position as religious guide and saint (pir-o-wilayat). They call him guru and from all sides fools and fraud-believers came to him and expressed their absolute faith in him. For three or four generations this shop had been kept warm. Several times it crossed my mind that either this false shop should be overthrown or should be brought into the ford of the people of Islam. (Nothing came of this) until Khusro passed that way (during his rebellion. This obscure mannequin determined to wait on him. At the place where he resided, Khusro too set up camp. He went and saw him (Khusro), conveyed to his ears irrelevant matters and with his finger put the saffron mark on his forehead which the Hindus call qashqa (i.e. tika) and consider auspicious. When this incident was reported to my elevated court, and I very well knew his falsehood, I ordered that he should be brought to me, and handed over his habitations, houses and children to Murtza Khan. Having brought his possessions under confiscation (qaid-i-zabt), I ordered that he be capitally punished.[iv]

The author of Dabistan-i-Mazahib, who was very familiar with Sikh traditions and on very good personal terms with the Sikh Gurus described the event in these terms:

For the reason that Arjan Mal (Guru Arjan) had given blessings to Prince Khusro, son of his majesty, who had rebelled against his father, His Majesty Nuruddin Muhammad Jahangir Padshah ordered that he be called to account and mulcted. A very large amount was demanded from him. The Guru was unable to pay it. He was, therefore, tied up in the desert (in the environs of) Lahore, and he died from the fierceness of the sun, heat of summer, and torture by the levy collectors. This happened in 1606-07 AD.[v]

On receiving the news of Guru Arjan Dev’s death, Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi wrote a letter to Murtza Khan (Shaikh Farid) with much jubilation, in which he says:

At this time the killing of accursed kafir of Govindwal, has been a very happy event. It is a matter of great defeat of the reprobated Hindus. For whichever reason he has been killed, and for whatever motive he has been put to death, the humiliation of kafirs is the very life of Islam.[vi]

Guru Hargovind, the next soldier-saint guru, sent for the Warrior-Brahman, Baba Praga, to his court. There were two armed clashes in which Mughal forces were defeated. Imperial forces made another attempt to capture him while Hargobind was stationed at Kartarpur. The renegade Painda Khan, who had earlier been the leader of Pathan mercenaries under the Guru, led the charge. (Ironically Painda Khan was like a cousin to Hargobind as the latter had been breast-fed by the former’s mother in his infancy). When Painda Khan dispersed the Sikh forces Baba Praga rallied them and with sword in hand engaged the enemy showing, with Nanda Sikh, much chivalry and valour. Painda Khan was killed in this encounter. In another battle against Jahangir’s forces Baba Praga was placed in charge of five hundred Sikhs to oppose the enemy. Baba Praga was severely wounded in this battle and died on return to his village. Suraj Parkash, Chapter 3 eulogises the role of Baba Praga in these events: Baba Praga chal kar aaya, kirpa drishti te gur warsad kare pach se sawar sang-keho karo tum aage jang. After the death of Baba Praga, his son Dwarka Das (or Durga Das) was anointed as the new Dewan of Guru Hargovind. With Jahangir’s death in 1627 his successor Shah Jahan proved even more hostile towards Hargovind

Guru Har Rai, the seventh guru, succeeded his grandfather at the age of fourteen, in 1644. He was mixed up in the war of succession between the sons of Shah Jahan, in favour of the loser Dara Shikoh. The next guru Hari Krishan aged five also died three years later, in 1664, while at Delhi on summons from Aurangzeb. Bhai Chaupat Rai, son of Bhai Pera, had accompanied the Guru to Delhi. Chaupat Rai (later Chaupa Singh) remained associated with the families of four gurus – from Hargovind to Gobind Singh – as teacher and body guard.

Tegh Bahadur succeeded Hari Krishan as the ninth guru. His envious cousins and nephews did not let him be in peace and he decided to travel eastward, till the atmosphere became more congenial in Punjab. Tegh Bahadur was an inveterate traveller. Earlier also he had been to Kurukshetra, Mathura, Agra, Prayag, Banaras, Gaya and Patna (1656 to 1664). Gaval Das son of Chhote Mal Chhibber, Chaupat Rai son of Pera Chhibber and Sangat son of Bina Uppal had accompanied him. (Bhatt Vahi Dakkhani).

Durgamal, son of Dwarka Das and grandson of Baba Praga, had been Dewan of Guru Har Rai and Guru Hari Krishan, till the time of Tegh Bahadur. At his request, he was relieved of his charge because of advancing age and his nephews Mati Das and Sati Das, sons of Qabool Das (Hira Nand in some documents) were appointed as Dewans by Tegh Bahadur. In December 1665 Tegh Bahadur started on a journey. Travelling through Agra, Allahabad, Banaras he reached Gaya. There he met Raja Ram Singh who was marching on Assam at the head of the Imperial army. At the invitation of the Raja, the Guru accompanied him, leaving his family at Patna. Along with Kirpalchand (maternal uncle), Bhai Chaupat Rai and Pandit Kirpa Ram Datt were left at Patna to take care of the family. Tegh Bahadur was at Dacca when he received the news of the birth of his son, Govind Rai (on December 22, 1666). During his return, in May 1667, he did not spend much time with his infant son at Patna because there were urgent messages for him to return to Punjab.

Aurangzeb had issued orders to governors of provinces to destroy temples and idols throughout his dominion and pressurize Hindus to convert to Islam. His experiment of converting India into a land of Islam was carried out with great vigour in Kashmir. The people there were facing atrocities and pressure from Iftikhar Khan, the governor, who was using force to convert the Pandits to Islam. Reduced to dire straits, a delegation came to Tegh Bahadur for help to save the Hindu religion. We quote here (in translation) from Bhatt Vahi Talauda Pargana Jind:

Kirpa Ram , son of Aru Ram, grandson of Narayan Das, great grandson of Brahm Das, of the house of Thakar Das of Bhardwaj gotra, Saraswat Datt Brahman Mulal (= Mohyal), resident of Matan, Pargana Srinagar, Kashmir, came to Chakk Nanki, Pargana Kahlur, on … 25 May 1675, bringing with him sixteen leading Brahmans of Kashmir. Guru Tegh Bahadur the Ninth Guru … consoled them.

Tegh Bahadur was aware of the deteriorating situation and he decided to take the bull by the horns. He advised the Kashmiri Pandits to tell the Mughal authorities that they would be willing to accept Islam if Guru Tegh Bahadur did the same. Orders for Guru’s arrest were issued by the Emperor while he was himself in the north-west subduing a rebellion by the Pathans. Tegh Bahadur was on a tour when he was apprehended. Bhatt Vahi Multani Sindhi as recorded by Girja Singh has the following entry (translation): “Guru Tegh Bahadur the ninth Guru … was taken into custody by Nur Mohammad Khan Mirza, of Rupar police post on … 12 July1675, at Malikpur Ranghran, Pargana Ghanaula, and sent to Sirhind. Along with him were arrested Diwan Mati Das and Sati Das, sons of Hira Nand Chhibber, and Dayal Das son of Mai Das.” The arrest near Sirhind is also corroborated by Kesar Singh Chhibber, in his Bansavlinama. On receipt of the news mother Nanaki deputed Dewan Dargah Mal Chhibber and Chaupat Rai Chhibber to hasten with Bhai Bhandari and bring further news.

MOHYAL MARTYRS

Gruesome actions of torture followed while the prisoners, who had been taken to Delhi, were asked to accept Islam. Bhai Mati Das was tied between two wooden planks while standing erect, slowly splitting his body into two by sawing it from head downwards. He faced the operation with composure, tranquility and fortitude. Bhai Dayala was boiled in oil and roasted alive. Bhai Sati Das was wrapped in cotton, soaked in oil, and burnt alive. Guru Tegh Bahadur had been made to witness all this to intimidate him but he refused to accept Islam. He was sentenced to death and executed on November 11, 1675 near the Kotwali in Chandni Chowk, Delhi. Martyrdom by Mati Das has no parallel in world history. Under centuries of foreign rule “the martyr remained an unsung and uncelebrated fugitive of history”. The descendants of the assassins of the much-mourned Imam Hussain had perfected more gruesome instruments of torture over a millennium.

Gruesome actions of torture followed while the prisoners, who had been taken to Delhi, were asked to accept Islam. Bhai Mati Das was tied between two wooden planks while standing erect, slowly splitting his body into two by sawing it from head downwards. He faced the operation with composure, tranquility and fortitude. Bhai Dayala was boiled in oil and roasted alive. Bhai Sati Das was wrapped in cotton, soaked in oil, and burnt alive. Guru Tegh Bahadur had been made to witness all this to intimidate him but he refused to accept Islam. He was sentenced to death and executed on November 11, 1675 near the Kotwali in Chandni Chowk, Delhi. Martyrdom by Mati Das has no parallel in world history. Under centuries of foreign rule “the martyr remained an unsung and uncelebrated fugitive of history”. The descendants of the assassins of the much-mourned Imam Hussain had perfected more gruesome instruments of torture over a millennium.

Gobind Rai was only nine years old when the severed head of his father was brought to Anandapur for cremation. To avoid the possibility of his capture as a hostage by Aurangzeb, the young guru and his entourage were moved further into the mountains at Paonta, where he spent many years of his childhood. It is stated that when Gobind Rai was anointed as the tenth guru, the first words he uttered were: “If there is anyone here descended from Mati Das let him stand up”. One Dharam Chand and Sahib Chand responding, the civil administration was given to the latter and the finances entrusted to the former. When Mukand Rai, the son of Mati Das, who was then at Karyala presented himself later before the Guru he was also appointed a civil minister. Dewan Sahib Chand always accompanied the Guru and was a great help in the field. He also performed the functions of Commander-in-Chief. In the Sikh Granths there is frequent mention of the heroic deeds of Sahib Chand. (Suraj Parkash, Chapter 3: Sahib Singh mahan bali jodha, Ap maran ko jodha hon krodha, Tis ke sang hazar karin hen, Maman Karn hath dharin hen … Dharam Chand liya kar Khizana, Sahib chand Ghar bar diwana …) Guru Gobind Singh also frequently mentions the valour and courage of Shahib Chand in the highest terms. (Russel Stracey pp. 28-29)

Gobind Rai married at the age of nineteen and had four sons – from his two wives Sundri and Jito. He moved back to Anandpur. Like his grandfather, Hargobind, he started gathering an army and fortifying his area. But the most important action was the formation on the sacred day of Baisakhi in 1699, the nucleus of a new community which was to be called the Khalsa – the pure. He baptized five men in a new manner. Their names were changed and given one family name “Singh”. Five emblems were prescribed for the Khalsa: kes, kangha, kachh, kara, kirpan. Sahib Chand, Dharam Chand, Chob Rai, and Chaupat Rai (all Chhibbers from the clan of Mati Das) were specially selected to assist. They were also baptized as “Singhs”, including Kirpa Ram Datta, who became Kirpa Singh. Thousands of Sikhs were baptized and the complexion of the Sikh community underwent a radical change.

Political power attracts reaction. The neighbouring hill Chiefs who were friendly with Guru Gobind, were alarmed by the growing power of the Khalsa as also fear of reprisals from the Mughal Emperor. There were several skirmishes with the local Chiefs. Bhai Sahib Chand (now Singh) and Bhai Dharam Chand/Singh were martyred in the battles during this period. The body of Sahib Singh was cremated by Guru Gobind Singh with his own hands on the bank of river Beas (Jit bhayi tahi Khalsa ki, Aru Sahib Chand ki loth uthayi). Soon thereafter the Guru sent the following firman to Gurbaksh Singh, the son of the martyr Dharam Singh, which document remained in the custody of the family till recent times:

Ek Onkar Sat Gur Ji, Siri Guru ji di agya hai Bhai Gurbaksh Singh, Kilor Singh Guru rakhega. Hukam dekhdyan … “May God protect Gurbaksh Singh Khilor Singh. The recitation of guru will ennoble life. On the receipt of this injunction Bhai Kaula other Dewan cousins and Sikh Khalsa or any other good man whom thou mayest like to bring with thee to my worship is welcome. Thou art the son of my noble disciple and thou hast found much favour in me. Thou and any other who may come with thee, will be entertained honourably. Don’t fear but come with freedom and easy mind. The reward of thy father’s services has been conferred on thee. One horse and 500 in cash are sent herewith through Attar Singh and Hira Singh attendants. Samvat 1716 dated Bhadur 12. Lines 14 ½. (Russel Stracey, p. 30)

Gurbaksh Singh, son of Dharam Singh, was then appointed Dewan – a post which his ancestors had held consistently over the generations. He remained with the Guru till Gobind Singh left for Deccan. Gurbaksh settled at his estate in Amritsar. He died in the battle when Ahmad Shah Abdali attacked Amritsar and destroyed Harimandar, during one of his invasions. A reference to this is available on pages 697-99 of Panth Parkash.

Aurangzeb would also feel uneasy with the growing strength of an unfriendly power-centre. Mughal army sent by subedars (district governors) of Sirhind and Lahore besieged Anandpur. After a stalemate, the Mughals offered Gobind safe conduct if he evacuated Anandpur. As would be expected, the enemy forces came in pursuit after he had gone some distance, ignoring their pledges sworn over the Quran. The Guru sent away his mother and two of the younger sons for safety and managed to reach the fortress of Chamkaur with a small band of about forty men. Pandit Kirpa Singh Datt (who had earlier come to Anandpur from Kashmir with a contingent of 500 fighters) was with the Guru at Chamkaur. According to Encyclopedia of Sikhism by Harbans Singh, Kirpa Singh Datt was martyred at this unequal battle at Chamkaur, along with Ajit Singh and Jujhar Singh, two elder sons of Gobind Singh. The Guru managed to escape to Jitpur through a stratagem. There he learned of the execution of his two remaining sons aged nine and seven by the governor of Sirhind. Thousands of Sikhs flocked to Guru’s camp after hearing of these dastardly murders and Gobind could spend about one year in peace at Dam Dama (breathing place). Here he busied himself with preparing a definitive edition of Granth Sahib and collecting his own writings which were put together by his disciple Mani Singh as Dasam Granth.

After losing these battles, the war was over at least for the present, so far as Guru Gobind Singh was concerned: that was the writing on the wall. In his Zafarnama, a letter full of defiance as also reprimand, he asked for justice from the Emperor expecting him to punish his officers who had been perfidious and treacherous in dealing with the Guru. He trailed Aurangzeb, and later Bahadur Shah, to Deccan expecting justice. It is difficult to fathom what exactly the Guru envisaged to extract from an adversary with whom he was (in fact their two dynasties were) locked in a life and death struggle. Convinced that Bahadur Shah, who had become the Emperor on the demise of Aurangzeb, would not take any action against his own officers, Guru Gobind stayed back at Nanded.

THE LAST MOHYAL RULER

Banda Veer Bairagi

Lachhman Dev, son of Ram Dev a Mohyal Brahman of Chhibber Caste, was born on 27 October, 1670 in village Mendhar, District Rajouri in Jammu and Kashmir. (Mendhar is now a border town on the Indian side on the Line of Control in Kashmir). As a Warrior-Brahmana (Mohyal), he was fond of hunting.[vii] Once when he killed a she-deer, he saw two off-springs falling from the womb of the female deer dying in pain. (Now a village called Harni i.e. a she-deer, exists at that place, atop a hill.) Deeply affected by the painful sight he reflected about the futility of his own life and activities. He decided to renounce the world and became a sadhu. Lachhman Dev was baptized as a sanyasi by Baba Janki Das at Rajauri and he performed tapassaya (austerities) near the bank of a river in the vicinity. Later he travelled from place to place, meeting saints and jogis. Finally coming to Nasik, on the bank of river Godavari, he came in contact with Yogi Augher Nath. There, Lachhman Dev was baptized as a Bairagi under the name of Madho Das. After some time he moved to Nanded (Maharashtra) where he established his own monastery and stayed for fifteen years. He must have attracted considerable following.

At Nanded, Madho Das Bairagi met Guru Gobind Singh in the last week of September 1708 and was deeply affected by the account of his struggle against Mughal despotism in Punjab. Gobind had witnessed two of his young sons being killed in a battle at Chamkaur and received news of the two younger sons being walled up alive in Sirhind. Madho Das must have seen the same pain in the eyes of Gobind as he had once witnessed in the eyes of the dying she-deer – and this encounter once again changed his life.

Guru Gobind Singh, a leader of men, immediately recognized “the fanatical gleam in the eyes” of the Bairagi and persuaded him to undertake to punish the men who had persecuted the Sikhs and murdered his sons. Being from North India it did not take long for Madho Das to grasp the situation.

Instant Commissioning of a Commander

Some Sikh and other scholars (like Khushwant Singh and W. H. McLeod) have been wondering how the Guru entrusted this job to a person so recently acquainted.[viii] Madho Das was a scion of the Chhibber clan of Mohyal Brahmanas though not belonging to the Baba Praga’s Chhibber family of Karyala. The Guru had great experience of the loyalty, valour and intrepidity of Mohyal Brahmans. Apart from Mati Das and Sati Das, the martyrdom of Sahib Singh Chhibber near Anandpur and Kirpa Singh Datt at Chamkaur must have been fresh on his mind. Gobind had always held the stock of Chhibber Brahmanas in high esteem: “Chhibbers are very dear to me.” He certainly had no misgivings about “investing Banda with full military and political authority to follow his own death.” And he took precautions to allay any possible reservations on the part of his followers back in Punjab. Banda was given “as a token of temporal authority a standard and a drum and a council of five advisers was appointed to assist him in the forthcoming conflict. A detachment of twenty five Sikhs was placed at his disposal as a bodyguard and a hukamnama was given to him calling upon all Sikhs to rally around him in his enterprise. Finally the Guru gave him his own sword, his green bow, and five arrows from his quiver.”[ix]

Mohyals were a group of small tribes (later castes). They did not have the numbers to invade and conquer any large kingdom on their own strength. And yet Mohyal sovereigns ruled in Sindh, Afghanistan and Punjab for long periods. How did they acquire these kingdoms? As will be observed from their history narrated in the previous chapters, each kingdom was almost “presented” to a Mohyal stalwart on the basis of the very first impression! A Brahmana refugee from Mathura presents himself in the office of the Brahmana Vazir (Chamberlain Ram) in Sind seeking employment and he is asked to draft a reply to a ‘diplomatic’ letter which was engaging the attention of the Vazir at that moment. Impressed by this first impression he gets a job in the Correspondence Department. Then the King confirms him as Assistant Secretary and later as Secretary-cum-Vazir on the basis of his first impression. On King’s demise the kingdom is presented to him by the Queen as the most suitable person available for her and the realm. This Brahmana, an ancestor of the present day Chhibbers and known to history as Chach, fully justified the confidence reposed in him by each of his benefactors. He ruled over the largest kingdom that Sindh ever had. A century later a Datta Mohyal Brahmana strayed into Kabul in Afghanistan. There had been a sort of revolution there. Another Brahmana Vazir, Kallar by name, had removed the King and was ruling directly. Spotting something in the personality of this youngster, Kallar commanded this stranger to conquer the northern region of Afghanistan (province of Mazare Sharif) which task he accomplished, of course with the help of “eight fold” forces provided by the state of Kabul. Later, Kallar anointed this commander (no relative) as the sovereign of Kabul under the name of Samanta Deva, in his own life time, and continued to act as Vazir. Guru Gobind Singh was not the first to delegate complete temporal authority to a Mohyal. The argument of propriety of having selected a man from his own flock is begging the question. He had located an extra-ordinary commander who he thought could win a war, which the Sikhs (his companions included) had lost signally, at least for the time being. He was not sending a newly recruited army.

Baptism of a Bairagi

There is another misconceived issue that the scholars labour out of sentiment rather than rationality. They argue could the Guru have entrusted such a responsible mission to someone without Pahul i.e. the ritual of Sikh baptism? The argument is conducted, for the most part, on the basis of what they think the Guru ought to have done.[x] Such slants are being introduced in Sikh history by the new ideology being developed by the Singh Sabha.

What was the purpose of this ritual? The Guru is stated to have declared:

Chidyaan naal je baaj laraavaan,

taan Gobind Singh naam kahavaan.

But in this case he was releasing, not a chidya, but a baaj (hawk) that he was blessing to fight not just one lakh but many lakhs, if necessary. Madho Das was a spiritual leader in his own right, with possibly a large following of his monastery at Nanded. With his earlier baptism as Bairagi, he did not need another. He did not give up his earlier beliefs: for example, he remained a Vaishnav and would not eat meat. It is doubtful if the two had time, during the Guru’s stay of a couple of weeks at Nanded, to exchange views about spirituality, peeree, even as a matter of interest between two saintly persons, which would have been the case if the political issues did not have urgency. Their interaction was about matters meeree – temporal. Banda did not violate any of the instructions specially conveyed by the Guru. As advised, every new action was commenced with Ardas, the supplicatory prayer of Sikhs to the almighty. In his humility he had introduced himself as the banda – slave – of the Guru, who in turn designated his new disciple as Banda Bahadur.

It should be recognized that Banda had his own persona inherited as a Warrior-Brahmana and conditioned by austerities (tapassaya) as an ascetic Bairagi. Guru Gobind certainly recognized these merits and kindled in him a new fire. If Gurus’s magic alone could create such a baaz, he would not have to leave Punjab, requesting restitution from his chief adversary.

Banda Bahadur in Punjab

With the blessings of the Guru, Banda proceeded northward with his small band. He halted at Sehra Khanda, just twenty five miles from the Mughal capital of Delhi. He sent hukamnama of Gobind to different part of the country, calling the Sikhs to join him in large numbers. Declaring his mission in the following words, he made his covenant with the people of Punjab: Aitak kaaj karaon jab mein tum, Janao mujhe tab he Gur-Banda.

To wreak vengeance on the Turk hath the

Guru sent me who am his slave;

I will kill and ruin Wazira’s household;

I will plunder and rob Sirhind.

I will avenge the murder of the Guru’s sons,

Then destroy the chieftains of the hills,

When all these I have accomplished, then

Know me as Banda, the slave of the Guru.

(Giani Gyan Singh, Panth Prakash)

Meanwhile Guru Gobind Singh had on 7 October, 1708 succumbed to the mortal attack by two Pathans, presumed to have been sent by the governor of Sirhind, who was apprehensive of rapprochement between Bahadur Shah and the Guru. This further inflamed Banda and the Sikh masses. Crowds flocked to his camp.

Banda moved along the Grand Trunk Road. At Sonepat he looted the state treasury and homes of the rich, and distributed everything among his men. Next, Samana was a wealthy town and the native place of Jalal-ud-Din, the executioner of Tegh Bahadur and Gobind’s two sons. The town was defended stubbornly for three days but all that remained were smoldering ruins and ten thousand corpses. Yielding considerable booty, Samana was the first notable victory by Banda.

Passing through Ghuram, Thaska, Shahbad and Mustafabad, Banda invaded Kapuri. The faujdar of this place had been notorious for his lustful campaigns. Kapuri was plundered and set on fire. At this time the Hindus of Sadhaura complained to Banda that the Muslims of that place had made their lives utterly difficult. Sadhaura received due punishment and the place is since known as Qatalgarh

But Sirhind was the accursed place, where every Sikh was longing to wreak a vengeance. Wazir Khan, the governor of this place, was responsible for the murder of Guru’s sons at Chamkaur and Sirhind. He collected forces from other faujdars in the region and came out to fight. Banda had no artillery, elephants or even sufficient number of horses. His army was largely composed of peasants armed with spears, swords, hatchets or farming implements which could be used as weapons. The two opposing forces met at Chhapar-Chiri. Wazir Khan had positioned his canons in front which started firing full blast. All booty-lovers in the ranks of the Sikhs fled. To stem the tide of desertion, Banda marched to lead the attack in person. His Sikhs charged the cannons and came to grips with the enemy. Wazir Khan was killed and the morale of his forces collapsed. It was a complete victory for Banda.

Two days later, Banda attacked and conquered Sirhind. Muslim writers complain, exaggeratedly, that the city was punished in a vindictive and barbarous manner. Banda, basically a saintly person, had not come on a mission of peace and reconciliation, nor were the sins being avenged ordinary crimes. The list of persons, butchered most inhumanly, in the families of the Gurus, and from within Banda’s own fraternity (Sati Das, Mati Das, Sahib Chand, Dharam Chand, Mukand Rai – all Chhibbers – and Kirpa Ram Datt, to name some) was pretty long. There is no record of any inhuman atrocity in Sirhind, whatever the number of persons killed.[xi] Anyway, Banda had redeemed his covenant with Punjab. He had avenged the murders of Guru’s sons (Laike vair guru putran da …) and punished Sirhind. Banda’s campaign was to be a game-changer. The local chiefs when they got an opportunity, and Nadirs and Abdalis continued to target the Hindu population, building even skull towers. But “fire had been put under the hoofs of Mughal horses” and the Mughal descendants of Bahadur Shah had lost control over this strategic gate-way to Delhi. This was the beginning of the end of Mughal rule in India.

Padshah Banda Bahadur

Banda was now the undisputed master of the territory between the Yamuna and the Satluj, with an annual revenue of 36 lakh Rupees. He fixed Mukhlaspur, near Sadhaura, as his headquarters. Banda’s was not just a punitive campaign. Sikh Raj had been established replacing the Mughal rule in Punjab. It had to have all the trappings of a kingdom – for the masses to accept, and respect, it as such. Sikh administrators had been appointed to administer the conquered areas. Banda started a new calendar dating from his capture of Sirhind. He had new coins struck to mark his reign, with Persian inscriptions on both sides:

Obverse: Sikka har do aalam tegh-i-Nank sahib ast

Fateh Gobind Singh shah-i-shahan fazl-i-sacha sahib ast.

Coins struck for the two words with the sword of Nanak

And the victory granted by the grace of Gobind Singh,

King of Kings and the true Emperor.

Reverse: Zarb ba amaan-ud-dahar masavrat

shahar zinut-ul-takht-i-mubarak bakht.

Struck in the heaven of refuge, the beautiful city,

The ornament of the blessed throne.

Very thoughtfully, Banda’s seal for official purposes had not only the names of the gurus but also the words degh and tegh, the popular symbols associated with the Sikh peeree and meeree:

Degh o tegh o fateh nusrat-i-bedrang

Yaft as Nank guru Gobind Singh.

Through hospitality and the sword to unending

victory granted by Nank and Guru Gobind Singh.

Hail to the humility and loyalty of a Bairagi. With unchallenged control over his kingdom, he proclaims to rule on behalf of the Gurus – like Bharat ruling in the name of Lord Rama, with the latter’s wooden sandals on the throne.

People came to Banda with their problems and these were redressed. Incessant victories of Banda Bahadur and his Sikhs created a terror among the Muslims. Such was the awe created in their minds that they began to believe him possessing some supernatural powers. Banda was a leader of the masses and needed them for his military operations in large numbers. If the devout, used to the tradition of earlier Sikh sangats, made any offerings he would redistribute it adding further to his appeal and aura – attracting more offerings. Peeree and meeree had been intertwined in the psyche of the rank and file of the Sikhs. Banda is being unfairly maligned for ambitions of guruship. For his mission to succeed, he needed to be accepted as the revered and undisputed leader, striding as a Colossus.

Some tillers of land near Sidhaura complained to Banda Bahadur about atrocities by their Muslim Zamindars. Banda asked them to stand in line and ordered Baj Singh to shoot them. Then with a violent voice shamed them that with such large numbers they could not put down a few Zamindars? This had the desired effect and within a few days no Zamindars were to be seen. This was the Bairagi’s innovative Pahul.

Encouraged by such reports, Sikhs in Jalandhar Doab also rose. They became the masters of Jalandhar and Hoshiarpur, even though one lakh Muslims had collected at Sultanpur, the capital of Doab. Removing Muslim officials at Batala, Kalanaur and Pargana of Pathankot, their swords reached the outskirts of Lahore. Overawed, the Faujdar of Lahore did not come out but Lahore was not invaded by the Sikhs. There is no explanation why the capital town of Lahore was spared at the crest of Sikh power.

The Mughal administration in Punjab had crumbled completely. Hearing of the large scale devastation Bahadur Shah abandoned his campaign in Rajasthan and moved north. Faujdars of Allahabad and Moradabad etc. were also asked to join him. Bahadur Shah and his successors, Jahandar Shah (1712) and Farrkah Siyyar (1713), continued to chase Banda Bahadur in plains and hills for the next few years, when they were not engaged in struggle for succession. Finally Banda Bahadur got trapped in the fortress of Gurdas Nangal, near Gurdas Pur and was captured after a long siege on 7 December, 1715. Banda and all Sikhs who could be rounded up were brought to Delhi in cages and chains.

Another Mohyal Martyr like Mati Das

Banda Bahadur was given the usual choice to accept Islam or to die, out of which he accepted the latter. His baby son Ajit Singh was dashed on the ground and its quivering heart thrust into Banda’s mouth. After this Banda’s right and then his left hand, his right and then left eye, were cut off and removed. His feet were similarly cut off. His body was torn to pieces with red hot irons and thus did this man of “undaunted valour” and bravery meet his death with exemplary coolness of mind[xii] and “glorifying in having been raised up by God to be the scourge of the inequities and oppression of the age.”[xiii] Did Sirhind witness anything even remotely approaching this type of revenge?

Banda Bahadur was given the usual choice to accept Islam or to die, out of which he accepted the latter. His baby son Ajit Singh was dashed on the ground and its quivering heart thrust into Banda’s mouth. After this Banda’s right and then his left hand, his right and then left eye, were cut off and removed. His feet were similarly cut off. His body was torn to pieces with red hot irons and thus did this man of “undaunted valour” and bravery meet his death with exemplary coolness of mind[xii] and “glorifying in having been raised up by God to be the scourge of the inequities and oppression of the age.”[xiii] Did Sirhind witness anything even remotely approaching this type of revenge?

Thus ended the life of Lachhman Dev Chhibber – adding another link, by no means the last one – in the chain of Mohyal martyres who willingly sacrificed themselves for the sake of justice and dharma.

Zamindari abolition. Banda’s rule had several lasting effects. Just as he distributed the offerings among the sangat and the booty among the soldiers, he distributed the land of big zamindars (who were Muslims) among the landless cultivators. This is the reason Punjab did not have Zamindari system, as for example in Uttar Pradesh.

Nanak instilled a feeling of self-respect among the down-trodden Hindus through bhakti and naam simran. Gobind Singh gave them the courage to fight against heavy odds. Banda gave them the zest to hold and administer land and not just loot or collect chouth like the Marathas. Gradually, the Sikhs organized themselves in Misls, or clan-militias, which marked out their respective areas of influence. Ranjit Singh consolidated these into a sovereign Sikh Raj, pushing his frontier beyond the Indus, which was during that period recognized as the Afghan territory.

Mohyal Tryst with Destiny

After ruling with power and glory for about two hundred years between Sirhind and Kabul, Mohyal Brahmanas had lost the area to the Ghaznavid Turks, in the early eleventh century. They had a tryst with destiny. Six centuries later, one of them Lachhman Dev Chhibber, a.k.a. Madho Das Bairagi a.k.a Banda Bahadur, reversed the tide and snatched back the governance of Punjab from the Mughals. He re-laid the foundation of a kingdom of Punjab to be ruled by the indigenous sons of the soil. Banda’s rule may have been short-lived but it was a game-changer. Thereafter the Sikh peasantry remained in constant rebellion. No descendant of Bahadur Shah could reign over Punjab. Ahmad Shah Abdali could humble the Mughal Emperor at Delhi but could not hold Punjab permanently even after defeating the Marathas. The course of Indian History would have been different if Punjab had submitted meekly to the Afghans as they had done to the Timurid Babar.

References and End Notes

THE SIKHS THE MUGHALS AND THE MOHYALS

[i] The foregoing account in this Section ‘RESISTANCE & MARTYRES.

[ii] While returning from Bhera, Babar attacked the Khokhars, at the behest of the Janjuas. Garh Thar Chak was destroyed during this operation.

[iii] T. P. Russel Stracey, The History of the Muhiyals, The Militant Brahman Race of India, p.22, quoting Sikh Parsang, Chapter III of Suraj Parkash: Sri Mukh ne updesh bakhana, Indriyan roko ho swadhana; swaas swaas simro ath jam, sab se ooncha aad guroo naam.

The other books consulted about Mohyal History are: Sikh Panth Ek Parichay (Hindi) by Dr. Lajja Devi Mohan (Gurgaon, 2007); P. N. BaLI, Mohyal History, 2006 Edition.

[iv] M. Athar Ali, Mughal India, quoted on pp. 188-89.

[v] M. Athar Ali, Mughal India, p. 190.

[vi] M. Athar Ali, Mughal India, p. 189.

[vii] Because he was fond of hunting, some scholars have assumed that Lacchman Dev (Banda) was a Rajput. Elsewhere also historians have tried, without justification, to ascribe Kshatriya varna to Mohyal Brahmanas (for example, the Hindu Shahis of Afghanistan) because they were good fighters and rulers.

Mendhar is a predominantly Gujjar (non-Muslims) area and there are no Dogra Rajputs in the vicinity. See Capt. Mangat Ram Chhibber, Sardar Bahadur, O. B. I., in Mohyal Mittar, December 1977, pp. 15-20.

[viii] W. H. McLeod, Essays in Sikh History, Tradition and Society (Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 79-81: “Who was this man who became known as Banda? … And was he previously known to the Guru? If not there was certainly a risk involved in entrusting so much authority to a person who was known only from first impression.”

Also, Khushwant Singh, A History of the Sikhs, Vol. I, p. 101, footnote: “Guru Gobind’s choice of Banda in preference to many of his own companions has never been adequately explained. From the chronology of Guru’s travels, it appears that he did not live more than on month in Nandid. It is hardly likely that he would have chosen a complete stranger unless he had either known of the man earlier or Banda had already earned the reputation of a leader.” (emphasis added)

[ix] W. H. McLeod traces these to Gian Sigh’s Panth Prakash and Tvarikh Guru Khalsa.

[x] W. H. McLeod, Essays in Sikh History, Tradition and Society, p. 80: “The problem becomes more acute when the question of Banda’s initiation into the Khalsa is raised … Was he or was he not given pahul? … the complete lack of references to Banda Singh may support this” (argument that Banda was not baptized as Sikh).

Of course there was neither the time nor occasion for this.

[xi] A hypothetical question is being raised, what treatment Guru Gobind Singh would have meted out to his arch enemies at Samana or Sirhind? And the discussion is being intentionally given a tendentious tinge by referring to a soft attitude towards Islam in the Guru Granth Sahib. These two have no connection. The Guru was definitely for punishing the enemies and he would not be devoid of the feelings that another father would have in such circumstances. Additionally, he would have been under an obligation to set an example for other tyrants, and Wazir Khan was not one of a kind. Sikh History is being re-written with a new perspective. “The Tat Khalsa section of the Singh Sabha movement ascended to dominance a hundred years ago and rewrote much of Sikh history in terms congenial to their particular point of view … they adopted a traditional view of History, correcting its emphasis and casting new interpretations in ways which they believed to be necessary.” W. H. McLeod, ibid., p. 18. So it is necessary to be discerning in choosing other sources for study of Sikh History.

[xii] W.L. M’Gregor, History of the Sikhs, Vol. I, p. 111.

[xiii] Mountstuart Elphinstone, History of India.

—–*—–

APPENDIX